Why Hedge Fund Managers Get Paid So Much Money

They're responsible for two very important jobs: Chief Investment Officer (CIO), Chief Risk Officer (CRO)

The best hedge fund managers rake in more than $1 billion per year.

There’s a reason hedge fund managers make so much money, and it’s not just because they wear Patagonia vests or have Bloomberg terminals running 24/7. It’s because they have to do two important jobs at once. Well, technically it’s one job—managing money—but money management is actually two jobs: making money (the Chief Investment Officer part) and making sure they don’t lose it all (the Chief Risk Officer part).

If you think about it, these two jobs are fundamentally at odds with each other. The CIO wants to floor the gas pedal, racing to generate the highest possible returns and dreaming of champagne-soaked performance fees. The CRO, on the other hand, is sitting there with their foot hovering over the brake, muttering about volatility and drawdowns and how investors won’t like it if the fund “blows up.” The CIO wants to win the race. The CRO just doesn’t want to die in a fiery crash.

Managing an investment portfolio is like driving a car up a winding mountain road. You want to go as fast as you can without flying off the cliff. Crucially, you can’t have one person pressing the gas (CIO) and another person working the brakes (CRO). That’s how you end up in the kind of situation where the car is wrapped around a tree and everyone’s yelling, “It’s not my fault!”

So hedge fund managers get paid a lot of money because they’re not just controlling the steering wheel and gas pedal; they’re also navigating, braking, and making sure the tires don’t explode.

The Gas and the Brake

Let’s start with the basics.

As an investor, the easiest way to make a lot of money—on paper—is to take on a lot of risk. Load up your portfolio with high-beta stocks and crypto, leverage it to the moon, and hope the market goes up. If it does, congratulations, your returns are through the roof. Of course, if it doesn’t, your fund might be down 80% by the end of the year, and your investors will not be thrilled.

On the flip side, the easiest way to avoid losing money is to take no risk at all. Buy some Treasury bonds or keep your portfolio in cash. You won’t blow up, but you’re also not going to impress anyone with your 4% annualized returns. Investors don’t pay hedge fund fees for Treasury-like performance.

So, the job of a hedge fund manager—whether they’re called the CIO, the CRO, or just “the boss”—is to navigate this tradeoff. They need to generate strong, market-beating returns without taking so much risk that the portfolio implodes. They need to know when to press the gas pedal and when to hit the brakes1.

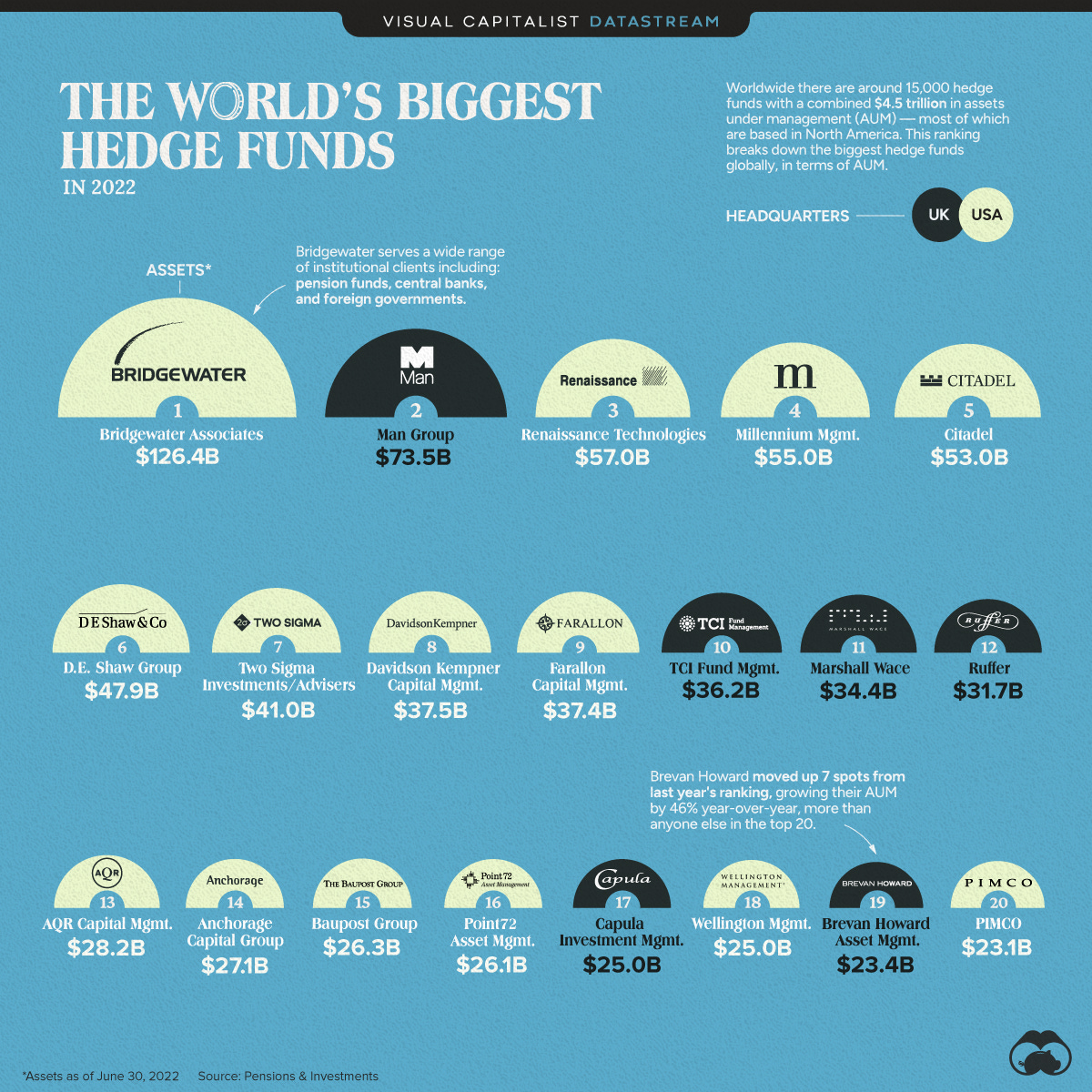

This is really hard to do! It’s why star hedge fund managers like Ken Griffin, David Tepper, or Steve Cohen can charge 2-and-202 (or more) and still have people lining up to give them money. They’re not just investors; they’re expert proverbial drivers, navigating a dangerous and uncertain road.

Why Splitting the CIO-CRO Roles Doesn’t Work

Given the dual nature of the job—maximize returns, minimize risks—you might think it makes sense to split the responsibilities into two roles. Have one person (the CIO) focus on making money and another person (the CRO) focus on risk management. Let the CIO press the gas and the CRO handle the brakes.

This seems logical. It’s also disastrous.

Let’s go back to the winding mountain road analogy. Imagine you’re in a car where one person controls the gas pedal, and another person controls the brakes. What happens?

Well, for one thing, there’s going to be a lot of arguing. The person with the gas pedal (the CIO) is going to want to go faster—“We’re falling behind! We need to take more risk!” The person with the brakes (the CRO) is going to want to slow down—“This curve looks dangerous! We need to reduce risk!” And if the car does crash, they’re both going to point fingers at each other.

Even if they don’t argue, the incentives are all wrong. The CIO is rewarded for generating returns, so they’re naturally going to push for more risk. The CRO is rewarded for managing risk, so they’re naturally going to push back. And if the CIO has more power—which they almost always do—the CRO’s warnings are likely to be ignored.

In other words, splitting the roles doesn’t create balance. It creates confusion.

The Directly Responsible Individual

The solution, then, is to combine the roles. Make one person responsible for both maximizing returns and managing risks. Make them the driver of the car—the person pressing the gas, working the brakes, and steering around the curves.

This idea is rooted in the concept of the “directly responsible individual” (DRI), which originates from Apple. If something goes wrong, there should be one person who is ultimately accountable. Not two people, not a committee, not some vague sense of shared responsibility. One person.

In a car, that person is the driver. In an investment portfolio, that person should be the fund manager. And just like the driver of a car, who gets injured or dies in the event of an accident, the CIO’s personal net worth should be invested in the same strategy they are using on behalf of their clients3. That “skin in the game” causes fund managers to be doubly cognizant of mitigating risks.

Why This Works

When the same person is responsible for both returns and risks, their incentives are naturally aligned. They can’t push the gas pedal too hard without considering the consequences, because they know they’ll be the one held accountable if the car crashes. They have to think holistically—balancing risk and return in real time, rather than treating them as separate objectives.

This is why the most successful hedge funds don’t separate the CIO and CRO roles. At Bridgewater, Ray Dalio wasn’t just making the investment decisions—he was also thinking deeply about risk. At Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett doesn’t have a separate CRO looking over his shoulder; he’s managing risk himself, whether he’s buying stocks or deploying billions of dollars in capital for acquisitions.4

Contrast this with firms that have struggled with risk management failures. In many cases, these failures can be traced to a star trader with little skin in the game being given a huge amount of capital to manage; if the trade makes money, the trader gets a huge bonus or cut of the profits, but if the trade loses money, the firm gets stuck with the losses5.

When no one is truly in charge of both returns and risks, bad things happen.

The Real Reason Hedge Fund Managers Get Paid So Much

So, why do hedge fund managers get paid so much money? It’s not because they’re just CIOs or just CROs. It’s because they have to be both.

They have to press the gas pedal and work the brakes. They have to balance risk and return in a way that few people can. They have to navigate the winding mountain road of investing with skill, judgment, and accountability.

They’re saddled with an enormous responsibility: achieve market-beating returns while controlling risk on a portfolio of assets worth billions of dollars.6

If they get it wrong—if they take too much risk and the portfolio blows up, or if they play it too safe and underperform the market—they’re the ones who get blamed.

Conclusion

Managing an investment portfolio is hard. It’s not just about making money—it’s about managing risk. And it’s not just about managing risk—it’s about making money.

So, the next time someone complains about how much hedge fund managers make, consider this: Would you feel safe as a passenger in a car where a remote control committee decides when to turn the steering wheel and hit the gas or brake? Or would you rather have one expert driver, navigating the road with skill and accountability?

That’s why hedge fund managers get paid so much money. Because they’re not just investors; they’re drivers who must safely speed on a dangerous mountain road, ensuring the car doesn’t fly off the cliff.

About

Inverteum Limited (HK) is a trading firm that specializes in long-short algorithmic strategies to generate returns in both bull and bear markets.

Inverteum has generated 52% annualized returns (39% after fees) since inception.

How We Invest

1. Minimize allocation to individual stocks due to their unpredictability

2. Build the most suitable trading strategy and go all in. Here's an example.

3. Be prepared for bear markets and ensure profitability during bad times by implement a short selling component to the strategy

And when to go in reverse (short sell), but there’s a limit to the analogy.

2% of assets and 20% of profits

Or hoarding cash. Berkshire now has $325 billion in cash.

The best source of these multi-billion dollar losses is Wikipedia’s list of trading losses.

Short list of trading losses and the nominal amount lost:

Morgan Stanley mortgage CDOs (2008): -$9b

JPMorgan London Whale (2012): -$6b

Amaranth Advisors (2006): -$6b

Thanks for this, I had an idea, but this is very well articulated. I can't wait to read more of your work.

Thanks for this. I get why the profession is demonised, but your conclusion is spot on IMO.